Push it to the Limit!

Published:

My first exposure to category theory was back in my first undergraduate course on abstract algebra. It was certainly ambitious of my professor to introduce students to group theory through a categorical lens, but I was absolutely hooked. Even now my research interests are very categorical in nature. However, there was one definition above all else that seemed a little more complicated to grasp: the notion of a limit.

I was always comfortable with universal properties, but for the longest time it did not sink in how limits were just instances of universal properties. Interestingly, the picture can be generalized to a slightly more involved setting, but it truly compactifies and captures the essence of what a limit really is.

In this post I will present the usual definition of a limit, then recall some other categorical definitions and show from them what a limit really is. I am of course assuming the reader has familiarity with basic notions of category theory. If you would like a review, I recommend taking a tour of the nLab, reading the classic book by Mac Lane, or more briefly going through these notes.

Without further ado, what exactly is a limit? To define limits we first need to define digrams of shape \(J\) and cones over a functor. Formally, a diagram of shape \(J\) in a category \(\mathcal{C}\) is just a functor \(F:J\to\mathcal{C}\). The reader might then wonder what’s the point of calling a functor by any other name? Well, one is typically interested in the case when \(J\) is a small or even finite category. Recall that a category is called small if its collection of objects is in fact a set; it is called finite if the objects are a finite set. But at the end of the day, yes, a digram is just another term for a functor. In these two particular cases of interest, especially the latter, the image of the functor can be neatly seen as just a diagram in \(\mathcal{C}\). By the defining properties of a functor, this diagram is clearly in the shape of \(J\).

Next, given \(F:J\to\mathcal{C}\) a digram of shape \(J\) in a category \(\mathcal{C}\), a cone to \(F\) is a pair consisting of an object \(A\) of \(\mathcal{C}\) and a family of morphisms \(\{\phi_{X}:A\to F(X)\}_{X\in\text{Ob}(J)}\) with the property that \(\phi_{Y} = F(f)\circ\phi_{X}\) for all morphisms \(f:X\to Y\). One typically denotes such a pair by \((A,\phi)\) with the assumption that \(\phi\) denotes the aforementioned family of morphisms.

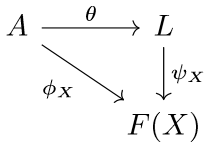

Now that we have cones, we can define a limit! A limit of the diagram \(F:J\to\mathcal{C}\) is a cone \((L,\psi)\) to \(F\) such that for every other cone \((A,\phi)\) to \(F\) there exists a unique morphism \(\theta:A\to L\) such that \(\phi_{X} = \psi_{X}\circ\theta\). That is, a limit of a diagram \(F\) is a cone to \(F\) such that all other cones to \(F\) factor through it. This can be expressed by the following diagram being everywhere commutative

Of course one can then dualize this notion and define cocones and analogously colimits, but these are just cones and limits in the opposite category, so I will solely consider these latter terms.

So what was so confusing to me about limits? Well more unsettling than confusing was actually the family of morphisms. To me, a limit of \(F\) is essentially an object of \(\mathcal{C}\) that combines all of the structure of \(J\). My reasoning is that not only does the limit map to every object in the image of \(F\), but these maps are furthermore compatible with the images under \(F\) of the morphisms as well. But having the equality \(\phi_{Y} = F(f)\circ\phi_{X}\) be the notion of compatibility was eery at first. Ironically, it also seemed familiar. It took me a while to realize where I had seen such a compatibility relation before: natural transformations!

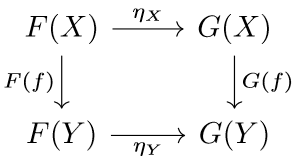

Recall that a natural transformation is in fact a morphism between functors which satisfies a compatibliity relation. Namely, if \(F,G:\mathcal{C}\to\mathcal{D}\) are functors, then a natural transformation \(\eta:F\to G\) is a family of morphisms \(\eta_{X}:F(X)\to G(X)\) for every object \(X\) of \(\mathcal{C}\) such that \(\eta_{Y}\circ F(f) = G(f)\circ\eta_{X}\) for all morphisms \(f:X\to Y\). The compatiblity is equivalent to the following diagram commuting:

The similarity to the compatibility relation in the definition of a limit should be rather striking. The problem is now how can I realize any cone \((A,\phi)\) as some sort of natural transformation? The way to do this is actually really trivial and the obvious thing to do once you know it…care to guess? Well let’s take a look at the compatibility relation once more: \((A,\phi)\) is a cone to \(F\) if \(\phi_{Y} = F(f)\circ\phi_{X}\) for all \(f:X\to Y\). I am now going to perform a wonderful trick:

\begin{equation*} F(f)\circ\phi_{X} = \phi_{Y} = \phi_{Y}\circ \text{id}_{A} \end{equation*}

As trivial as this insertion of the identity morphism might appear, it immediately presents the underlying natural transformation structure going on here. If I want this to be a statement about a natural transformation, I obviously need another functor besides the diagram \(F: J\to\mathcal{C}\). Given the above equality, I will define the following functor \(G:J\to\mathcal{C}\) where I assign every object of \(J\) to the same object \(A\) and to every morphism of \(J\) I will just map them all to the identity morphism of \(A\). This is commonly called the constant functor and denoted by \(\Delta(A)\).

This is it! Now every cone is in fact nothing more than a natural transformation from a choice of a constant functor! That is, \((A,\phi)\) is a cone to \(F\) if and only if \(\phi:\Delta(A)\to F\) is a natural transformation. If every cone is simply a natural transformation, then what does this say about limits?

In order to address this, let us take one step further in this generalization and define the following functor: \(\Delta:\mathcal{C}\to\mathcal{C}^{J}\), where the codomain category is the category of functors from \(J\) to \(\mathcal{C}\), and \(\Delta: A\mapsto \Delta(A)\). One might be wondering why would I create such a functor? Weren’t the \(\Delta(A)\) functors enough? Now I have a functor into functors??? Yes, this is exactly what we’re missing! One must recall that functors do not simply associate objects between categories, they must also map morphisms in a compatible way!

In particular, in order for my proposed functor \(\Delta\) to actually be a functor, I need to define what happens to any morphism \(\varphi:A\to B\). Well, the target category is a category of functors, so \(\Delta(\varphi):\Delta(A)\to \Delta(B)\) must be a natural transformation. Thus, it is equivalent to define a family of component morpshisms that satisfy the definition of natural transformation. To this end, if \(X\) and \(Y\) are objects of \(J\), then \(\Delta(A)(X) = A = \Delta(A)(Y)\) and \(\Delta(B)(X) = B = \Delta(B)(Y)\). Moreover, for any morphism \(f:X\to Y\) we have \(\Delta(A)(f) = \text{id}_{A}\) and \(\Delta(B)(f) = \text{id}_{B}\). Hence, the components \(\Delta(\varphi)_{X}\) must satisfy

\begin{equation*} \text{id}_{B}\circ\Delta(\varphi)_{X} = \Delta(\varphi)_{Y}\circ\text{id}_{A} \end{equation*} which is to say, every component morphism needs to be the same! Well, given that we started with a morphism \(\varphi:A\to B\), we can just take the natural transformation to have all components equal to \(\varphi\)! Thus, \(\Delta\) is a functor defined by mapping each object of \(\mathcal{C}\) to the corresponding constant functor, as well as mapping each morphism in \(\mathcal{C}\) to the constant natural transformation whose components are all the input morphism!

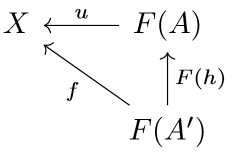

To finish, recall the notion of a universal morphism from a functor (resp. object) to an object (resp. functor). For the purpose of this blog, I will only define the former object; the latter is obtained by reversing arrows. Given a functor \(F:\mathcal{C}\to\mathcal{D}\), a universal morphism from \(F\) to \(X\) with \(X\) an object of \(\mathcal{D}\) is a pair \((A,u: F(A)\to X)\) consisting of an object from \(\mathcal{C}\) and a morphism \(u:F(A)\to X\) in \(\mathcal{D}\) such that for any morphism \(f:F(A’)\to X\) in \(\mathcal{D}\), there exists a unique morphism \(h:A’\to A\) in \(\mathcal{C}\) such that the following diagram commutes

This construction might be familiar to those who know about comma categories, but I do not need this much generality here and will thus now discuss it. Indeed, now that we have recalled universal morphisms, we are done! Returning to our previous setup, we had a diagram \(F:J\to\mathcal{C}\), which is nothing more than an object in the category \(C^{J}\). We then defined the constant functor \(\Delta:\mathcal{C}\to \mathcal{C}^{J}\), and are able to phrase a limit as being a natural transformation \((\Delta(L),\psi)\) to \(F\) such that all other natural transformations \((\Delta(A),\phi)\) to \(F\) uniquely factor through \((\Delta(L),\psi)\) i.e.

A limit of \(F\) is a universal morphism from \(\Delta\) to \(F\).

This might seem more complicated to some, but in my opinion it makes sense to actually define a limit first as a universal morphism from this constant functor, and then simplify and unpackage what all of this means. One indeed obtains the usual definition of a limit, but again that definition seems sort of odd. Universal morphisms also provide more intuition. A universal morphism from a functor to an object is just the existence of an object in one category whose image is closest to a prescribed object in the other category. This is why all other images factor through this closest one. Thinking about limits, we are looking for a constant functor that is closest to the given diagram, but the constant functor is equivalent to a single object. This furthers my previous comment that a limit is essentially an object that combines, or perhaps embodies, all of the structure of \(J\). Examples of limits like products, equalizers, and pullbacks also agree with this perspective.