Monoids are Algebras, Change My Mind

Published:

One of my favorite parts about Category Theory is its generalization of commonly seen structures or interactions, and then being able to witness similar behavior in surprisingly different context. This blog post pertains to one particular categorification I like: monoid objects and module objects with respect to a monoid object.

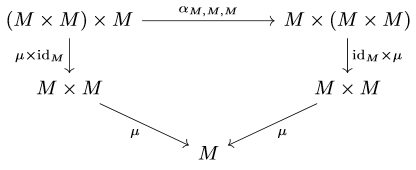

As the name suggests, one looks at a categorification of a monoid, which is just a group with no inverses or a semigroup with an identity; it depends on how you see the glass of water I suppose. No matter what’s in your cup, a monoid is a set with a unital, associative, binary product. Like most things in category theory, the general construction we are aiming for can be obtained if you consider what the structure is in terms of maps; after all, categories are all about morphisms!

If we denote a monoid by \(M\), then that there is a binary operation means there is a set-map

\begin{equation*} \mu:M\times M\to M, \end{equation*}

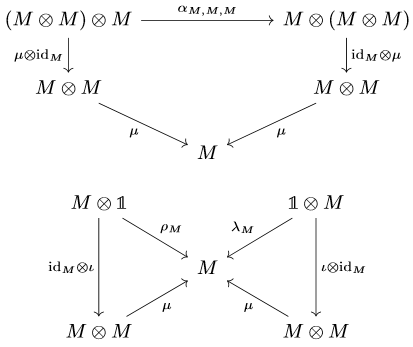

and its associatitivity means the following diagram commutes

where \(\alpha_{M,M,M}\) is the canonical isomorphism. The fact that the operation is unital means that there is a two-sided identity element with respect to the operation. Now, recall the one-element set \(\mathbb{1} := \{\ast\}\) and the unique set-map \begin{equation*} \iota:\mathbb{1}\to M,\quad \ast\mapsto 1_{M} \end{equation*} Then the unitality of \(\mu\) means the following diagrams commute

where \(\rho_{M}: (m,\ast)\mapsto m\) and \(\lambda_{M}:(\ast, m)\mapsto m\).

Now, how can we proceed to generalize this to consider monoids in any category? Well the first thing to note is that there is a huge dependence on the categorical structure of \(\textbf{Set}\). In particular, it was utilized that \(\textbf{Set}\) has a product and a singleton set that can embed nicely into any monoid. Moreover, there are very important morphisms that one otherwise takes for granted if the diagrams are not explicitly drawn. These are the maps \(\alpha_{M,M,M}, \rho_{M},\) and \(\lambda_{M}\). Indeed, writing the definition of a monoid in terms of elements, one does not really acknowledge the presence of these “structural maps.” However, they are the bread and butter of what it means to be a monoid! The operation being associative is captured by the compatibility of \(\mu\) with the associativity map, and the unitality is captured by the compatibility of \(\mu\) and \(\iota\) with \(\rho_{M}\) and \(\lambda_{M}\).

Thus, the minimal requirement on a category in order to have a monoid object is that the category should be monoidal; that’s easy to remember! If we have a monoidal category \((\mathcal{C},\otimes,\mathbb{1},\alpha,\rho,\lambda)\), then one calls \((M,\mu,\iota)\) a monoid object if the following diagrams commute

These are precisely the diagrams above, so a monoid object in \(\textbf{Set}\) is the classical monoid as we expect.

Now that we have this generalized notion of a monoid object, what are some examples in other categories? It is a fun exercise to verify the following instances of monoid objects:

- In \(\textbf{Ab}\), a monoid object is an associative, unital ring.

- In \(R\)-\(\textbf{mod}\), a monoid object is an associative, unital \(R\)-algebra, which is consistent with the previous bullet.

- In \(\textbf{Mon}\), the category of monoids, a monoid object is in fact a commutative monoid! Compare this to the case of what a group object is in the category of groups \(\textbf{Grp}\).

- In a category with finite coproducts, every object can be trivially made into a monoid.

- In \(\textbf{End}_{\textbf{Cat}}(\mathcal{C})\), the category of endofunctors of \(\mathcal{C}\), a monoid object is a monad.

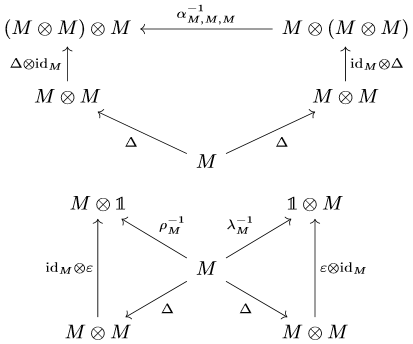

There are now a few things we can do, two of which are natural, and another is partially motivated by the above instances of monoid objects. The first is like with every categorical object defined via morphisms, we can equally define its dual by reversing the arrows. In particular, for a monoidal category \(\mathcal{C}\) as above we define a comonoid object as a triple \((M,\Delta,\varepsilon)\) such that the following diagrams commute

and as with most dual objects, a monoid object in the opposite monoidal category \(\mathcal{C}^{\text{op}}\) is a comonoid object in \(\mathcal{C}\). In the examples of monoid objects above, the corresponding comonoid objects are simply \(R\)-coalgebras, etc.

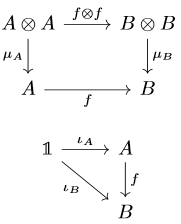

The other natural thing we can do is look at the category of monoid objects over a monoidal category. To do this, we first need to define what are morphisms between monoid objects. Again being motivated by the classical definition of monoid homomorphisms, which we take to fix the identity element, the natural choice of morphisms between monoid objects is as follows. Suppose \((A,\mu_{A},\iota_{A})\) and \((B,\mu_{B},\iota_{B})\) are monoid objects in \(\mathcal{C}\). Then a morphism \(f\in\text{Hom}_{\mathcal{C}}(A,B)\) is a morphism of monoid objects if the following diagrams commute

If one considers \(\mathcal{C} = \textbf{Set}\), then \(f\) is indeed a monoid homomorphism in the aforementioned classical sense.

Now with this, one can take the subcategory \(\textbf{Mon}_{\mathcal{C}}\) of monoid objects of \(\mathcal{C}\) with morphisms of monoids. This will not necessarily be a full subcategory because the morphisms have to satisfy the above compatibility with the monoid object maps. Analogously there is the subcategory \(\textbf{CoMon}_{\mathcal{C}}\) of comonoid objects of \(\mathcal{C}\). What is interesting is that as \(\mathcal{C}\) is a monoidal category, one might wonder whether either \(\textbf{Mon}_{\mathcal{C}}\) or \(\textbf{CoMon}_{\mathcal{C}}\) is similarly monoidal. I recommend the reader to show that the unit object is a (co)monoid object. However, the tensor product of two monoid objects need not be a monoid object. Even if they were, it is not immediate that the associator and left- and right-unitors of the original monoidal category should be morphisms of (co)monoid objects as well, so one might need a different set of “structural maps” for these subcategories.

Interestingly enough, if we further assume we are looking at monoid objects in symmetric monoidal categories, then suddenly we may indeed show that the categories \(\textbf{Mon}_{\mathcal{C}}\) and \(\textbf{CoMon}_{\mathcal{C}}\) are monoidal categories! At the very least, proving that the tensor product of monoid objects is a monoid object becomes very straightforward. What about making tensor products of monoid objects in a braided monoidal category? As it turns out, the tensor product of monoid objects is still a monod object, but how one defines the corresponding multiplication requires a bit of care as one intends to utilize the hexagon axioms in proving the resulting object is indeed monoidal.

What about the third thing I mentioned one could do with monoid objects? Well, given the examples of monoid objects above, one can further study monoid objects by categorifying the notion of modules. That is, we can develop a representation theory for monoid objects by defining module objects for a monoid object in a monoidal category! However, this is actually a far deeper categorification than what one might expect i.e. one can discuss the notion of enriched categories. I will carry this on in a future blog post!