What is a Hopf Algebra?

Published:

The goal of this blog post is to present the definition and basic consequences therein of a Hopf algebra. For those that read more of my blog posts, this post and this one are some preliminary notions and results for some awesome blog posts to come. Without further ado, what is a Hopf algebra?

Now, to the best of my knowledge there are a few ways to introduce Hopf algebras. The one I will present here is sort of categorical, but not too demanding if the reader is uncomfortable with category theory. Moreover, the motivation for why one considers Hopf algebras at all is actually one of the points I emphasize here. Otherwise, admittedly the structure I will define might seem sort of “forced;” as if I am constructing it just for fun with no purpose. Well for now, what’s wrong with a little fun?

The tl;dr is that a Hopf algebra is a bialgebra with an antipode.

To flesh out the details, let us first recall what is an associative unital \(R\)-algebra over a commutative (associative and unital) ring \(R\). In particular, as \(R\) is assumed to be commutative, there is no distinction between left and right \(R\)-modules. Then abstractly, an associative unital \(R\)-algebra is a monoid object in the category of \(R\)-modules. More commonly (but equivalently!), an associative unital \(R\)-algebra is a triple \((A,\mu_{A},\iota_{A})\) consisting of an \(R\)-module \(A\) with an \(R\)-bilinear map \(\mu_{A}: A\otimes A\to A\) and an element \(1_{A}\) such that

- \( \mu_{A}(\mu_{A}(a,b),c) = \mu_{A}(a,\mu_{A}(b,c))\)

- \( \mu_{A}(1_{A},a) = a = \mu_{A}(a,1_{R})\)

Some readers might be familiar with a slightly different formulation of an associative unital \(R\)-algebra, but I’m sure your notion is equivalent to this. The reason why I like this formulation is that it makes it really easy to define a coalgebra when you express the above conditions in terms of diagrams. To do this, we need to point out a couple of subtleties with these two conditions.

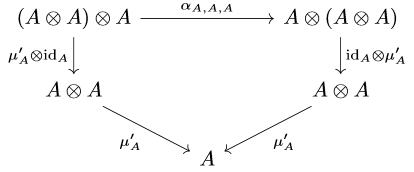

For the first, recall that \(\mu_{A}\) is required to be \(R\)-bilinear. By the universal property of tensor products, there is an induced \(R\)-linear map \(\mu_{A}’: A\otimes A\to A\) such that on a simple tensor \(x\otimes y\mapsto \mu_{A}(x,y)\). This then allows one to define an \(R\)-linear map on \((A\otimes A)\otimes A\) and \(A\otimes (A\otimes A)\), both to \(A\otimes A\), given by \(\mu’_{A}\otimes\text{id}_{A}\) and \(\text{id}_{A}\otimes\mu’_{A}\). Since linear maps from a tensor product are equivalent to bilinear maps from the underlying direct product, \(\mu_{A}’\) uniquely determines \(\mu_{A}\) and the associativity is equivalent to

\((\mu_{A}’\circ(\mu’_{A}\otimes\text{id}_{A}))((a\otimes b)\otimes c) = (\mu_{A}’\circ(\text{id}_{A}\otimes\mu_{A}’))(a\otimes (b\otimes c))\)

Now, going back to the subtlety I was promising: the equality in 1 is not on the same triple of elements! Indeed, the above expression in terms of tensor maps shows the domain of the left hand side and right hand side are \((A\otimes A)\otimes A\) and \(A\otimes (A\otimes A)\), respectively. These spaces are not the same spaces, but they are isomorphic as \(R\)-modules! If we turn to the language of diagrams, the associativity of our multiplication is equivalent to the commutativity of the following diagram

For the second condition, recall that having this unit allows one to define the following \(R\)-linear map \(\iota_{A}: R\to A\) given by \(r\mapsto \phi(r)(1_{A})\) where \(\phi: R\to\text{End}(A)\) is the \(R\)-module structure on \(A\). In particular, note that since \(\phi\) is a ring homomrphism and preserves the identity

\(\iota_{A}(1_{R}) = \phi(1_{R})(1_{A}) = \text{id}_{A}(1_{A}) = 1_{A}\)

From this, the \(R\)-linearity of \(\iota_{A}\), the \(R\)-bilinearity of \(\mu_{A}\), and that \(1_{A}\) is a unit implies \(\iota_{A}\) has its image contained in the center of \(A\):

\(\mu_{A}(\iota_{A}(r),x) = \mu_{A}(\phi(r)(\iota_{A}(1_{R})),x) = \phi(r)(\mu_{A}(1_{A},x)) = \phi(r)(x)\)

similarly

\(\mu_{A}(x,\iota_{A}(r)) = \mu_{A}(x,\phi(r)(\iota_{A}(1_{R}))) = \phi(r)(\mu_{A}(x,1_{A})) = \phi(r)(x)\)

Thus, the image is in the center and in particular

\begin{equation} \mu_{A}(\iota_{A}(r),x) = \phi(r)(x) = \mu_{A}(x,\iota_{A}(r)) \end{equation}

Using juxtaposition, equation (1) is more commonly written as \((r1_{A})x = rx = xr = x(r1_{A})\). Note that the center term of (1) is in fact \(R\)-bilinear in the arguments, hence lifts to a linear map on the corresponding tensor product. In particular, (1) is equivalent to the following diagram being commutative

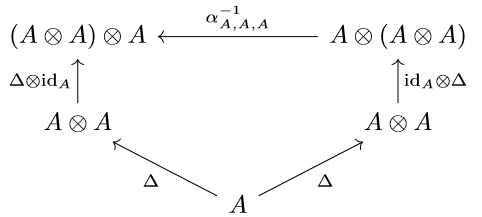

One can in fact define an associative unital \(R\)-algebra as a triple \((A,\mu_{A},\iota_{A})\) consisting of an \(R\)-module \(A\) with an \(R\)-bilinear map \(\mu_{A}: A\otimes A\to A\) and an \(R\)-linear map \(\iota_{A}:R\to A\) such that the above diagrams commute. In other words, like I said before: as a monoid object in the category of \(R\)-modules! It should now be evident how one defines a coalgebra: just dualize the diagrams! More specifically, a coassociative, counital \(R\)-coalgebra is a triple \((A,\Delta_{A},\varepsilon_{A})\) consisting of an \(R\)-module \(A\) with \(R\)-linear maps \(\Delta_{A}: A\to A\otimes A\) and \(\varepsilon_{A}:A\to R\) such that the following diagrams commute

The reader should try to guess what a bialgebra is before going on.

Did you guess? If you thought it would be a quintuple \((A,\mu_{A},\iota_{A},\Delta_{A},\varepsilon_{A})\) consisting of an \(R\)-module \(A\) with an \(R\)-bilienar map \(\mu_{A}: A\otimes A\to A\) and \(R\)-linear maps \(\iota_{A}:R\to A\), \(\Delta_{A}: A\to A\otimes A\), and \(\varepsilon_{A}:A\to R\), then you are almost correct! The only other part of the definition is that there is some compatibility between these operations. Namely, a bialgebra is a quintuple as expected, except it further satisfies any one of the following equivalent conditions

- \(\mu_{A}\) and \(\iota_{A}\) are coalgebra homorphisms.

- \(\Delta_{A}\) and \(\varepsilon_{A}\) are algebra homorphisms.

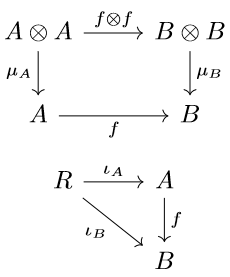

In category theory terms, a bilagebra is a bimonoid in the category of \(R\)-modules; a monoid in the category of comonoids in \(R\)-mod; a comonoid in the category of monoids in \(R\)-mod. One little detail I am bypassing is what exactly is an algebra or coalgebra homomorphism; what are the morphisms in the aforementioned categories? Well, these are exactly what you would imagine: \(R\)-linear maps that preserve the (co)algebra structure! Namely, \(f\) is an algebra homomorphism or coalgebra homomorphism if the following diagrams commute

respectively.

Before going on to defining a Hopf algebra, I would like to comment on the notion of algebra and coalgebra just defined. Namely, one might be use to commutative algebras, which is an (associative unital) algebra such that

\(\mu_{A}\circ P = \mu_{A}\)

where \(P:A\otimes A\) is the usual swap in \(R\)-modules i.e. \(x\otimes y\mapsto y\otimes x\). Similarly, there is a notion of cocommutative coalgebras by requiring that

\(P\circ\Delta_{A} = \Delta_{A}\)

For a discussion on the categorical significance of the transpoition map, I invite the reader to check out this post. The only reason I point out the idea of (co)commutativity is that it is not a requirement for the (co)algebra structure, and hence not required for biagebras of Hopf algebras. If the underlying (co)algebra is (co)commutative, then one similarly says that the bialgebra or Hopf algebra is (co)commutative.

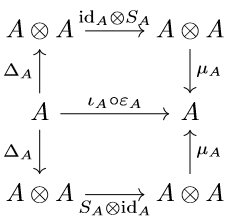

Alright, well now that we have bialgebras, how do we get Hopf algebras? The progression from algebra to coalgebra and then to bialgebra seems pretty natural. To summarize, we formulate the axioms of an algebra in terms of diagrams, dualize them, and then consider objects that satisfy the corresponding four diagrams with a compability condition. So what is the “additional thing” done in order to obtain a Hopf algebra? Unfortunately, at the present time the definition will seem rather forced. It will be demystified in future blog posts, so for now take it as you would like: a Hopf \(R\)-algebra is a sextuple \((A,\mu_{A},\iota_{A},\Delta_{A},\varepsilon_{A}, S_{A})\) such that the first five maps make \(A\) an \(R\)-bialgebra, and where the \(R\)-linear map \(S_{A}:A\to A\) is such that following diagrams commute

Of course, one naturally has the categorical notion of Hopf monoid, but that is probably not surprising at this point. What is interesting though is that if an antipode exists, then it is unique. Also, from its definition alone, antipodes are necessarily antihomomorphisms of algebras and coalgebras. Seeing how richly defined a Hopf algebra is, it should not come as a surprise that the representation theory of a Hopf algebra is also quite rich. I will have more to say in future blog posts about its categorical significance, but for now I would like to present two fundamental examples of Hopf algebras before finishing off this post.

The reader familiar with finite groups or Lie algebras should know about group algebras and universal enveloping algberas, respectively. Otherwise, you can check out their definitions here and here, respectively. I encourage the reader to then verify that if \(G\) is a finite group and \(\mathfrak{g}\) is a complex Lie algebra, then the group algebra \(k[G]\) and universal enveloping algebra \(U(\mathfrak{g})\) can be made into Hopf algebras. These two families of examples are actually fundamentally important to the general theory of Hopf algebras because of the following theorem attributed to Cartier, Gabriel, and Kostant:

Theorem Suppose \(H\) is a cocommutative Hopf algebra over a characteristic zero algebraically closed field \(k\). Then there is an isomorphism

\begin{equation*} H\cong U(P(H))\ltimes k[G(H)] \end{equation*}

where \(P(H)\) is the Lie algebra of primitive elements of \(H\) and \(G(H)\) is the group of grouplike elements of \(H\).

The proof is surprisingly straightforward and provided in Etingof. I would like to make a blog post about this since I have never really hashed out the details; I was just shocked when I read this and never forgot. Indeed, an immediate corollary is if the only grouplike element of a Hopf algebra is its multiplicative identity, then \(H\) is actually a universal enveloping algebra. That’s pretty remarkable!